It’s Eventuary all month long at ThoughtWorks Australia. We have so many projects incorporating Event Driven Architecture underfoot that we thought we would celebrate and share our insights.

Event Driven Architecture is gaining popularity again as teams look for ways to simplify the coordination of their microservices. Add to this the growing popularity of Kakfa, we get many teams beginning to explore Event Driven Architectures for the first time.

Today I am taking a look at several complementary concepts that fall under the Event Driven Architecture (EDA) umbrella. I have been working as an Architect in a team that is starting their EDA journey. I compiled this terminology explanation for them to help unpack the many connected concepts.

Some of these concepts govern a high-level macro architecture (how our system hangs together) and others are closer to code, micro architecture (what our system does). We can consider the macro architecture the Big Boxes, and how they work together, whereas the micro architecture governs what is happening inside the box.

For the purpose of this explanation, I’ll explore these concepts through the lens of a Restaurant.

Higher Level/Macro Architecture

Microservices/Self Contained Services

Microservices is a term which was pioneered around 2011, and has gained steady traction to date. In its essence, it is about defining boundaries around your code to deploy and develop smaller services in order to improve the quality of the end product.

The size of the service (the micro part) is often questioned - just how small do we make this? At an extreme is the notion that services are so very small they could be rewritten easily within a day.

Instead of considering the size of each service, focus on the boundary between services. The boundary should be informed by the Business Context and the Business Capabilities it supports.

In our Restaurant example, our Bounded Contexts (and therefore services) might be:

- the Kitchen

- the Waiter

- the Cashier

- the Stockroom

Each service is responsible for managing its own data, its business processes and its UI.

We are not aiming for homogenous SCS, but would rather select an appropriate technology (however the technology choices are governed by our Tech Radar).

Event Driven Architecture

Now we have defined our self contained services for our domain, there are times when the end of a process in one service triggers the start of a process within another service. After all, in our restaurant domain, the Stockroom needs to know what food the kitchen is using to know when to restock, and the cashier needs to know what was ordered in order to prepare the bill.

One method is for the microservices to call each other to trigger business processes within different services. But that couples the services to each other, to the point where it can be difficult to understand how to develop locally without all the microservices, releases result in deploying all services and it ends up in a big tangled mess.

We can do better.

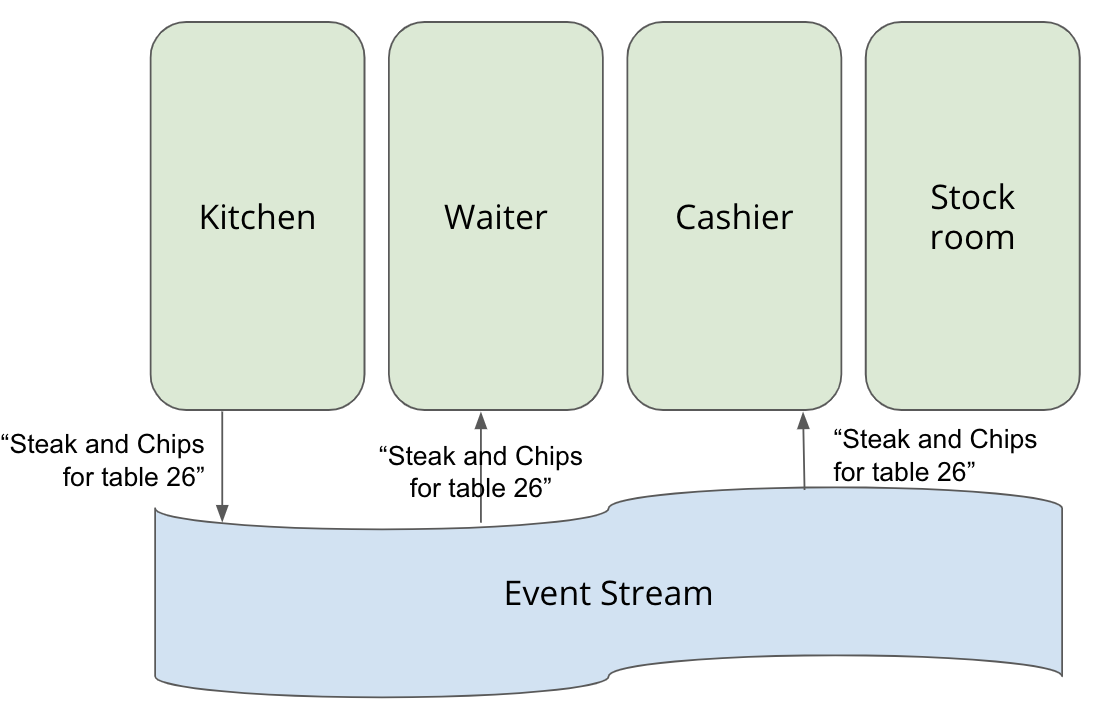

Once a service finishes its process, it can shout what it just did. The Kitchen shouts out “Steak and Chips for table 26”. That’s the end of Kitchen’s involvement. It doesn’t know or care what happens in the rest of the system. The Cashier hears the message and adds $35 to the bill for Table 26. The Waiter hears the message, and delivers a plate of food to table 26.

Now the Kitchen, Cashier and Waiter are loosely coupled to each other by the broadcasting of the Event. It simplifies our development and testing, as we don’t need to have the whole system running in order to develop locally, we can release each service independently, and the communication between each service is simplified and easier to understand.

This is Event Driven Architecture.

Event Driven Architecture is an architectural paradigm in which the system changes in reaction to events that have happened. This allows us to create loosely coupled software components and services and describes how small independent business processes are choreographed. Components in a loosely coupled system are quicker to build, easy-to-understand and simpler to test.

Anatomy of an Event Driven system

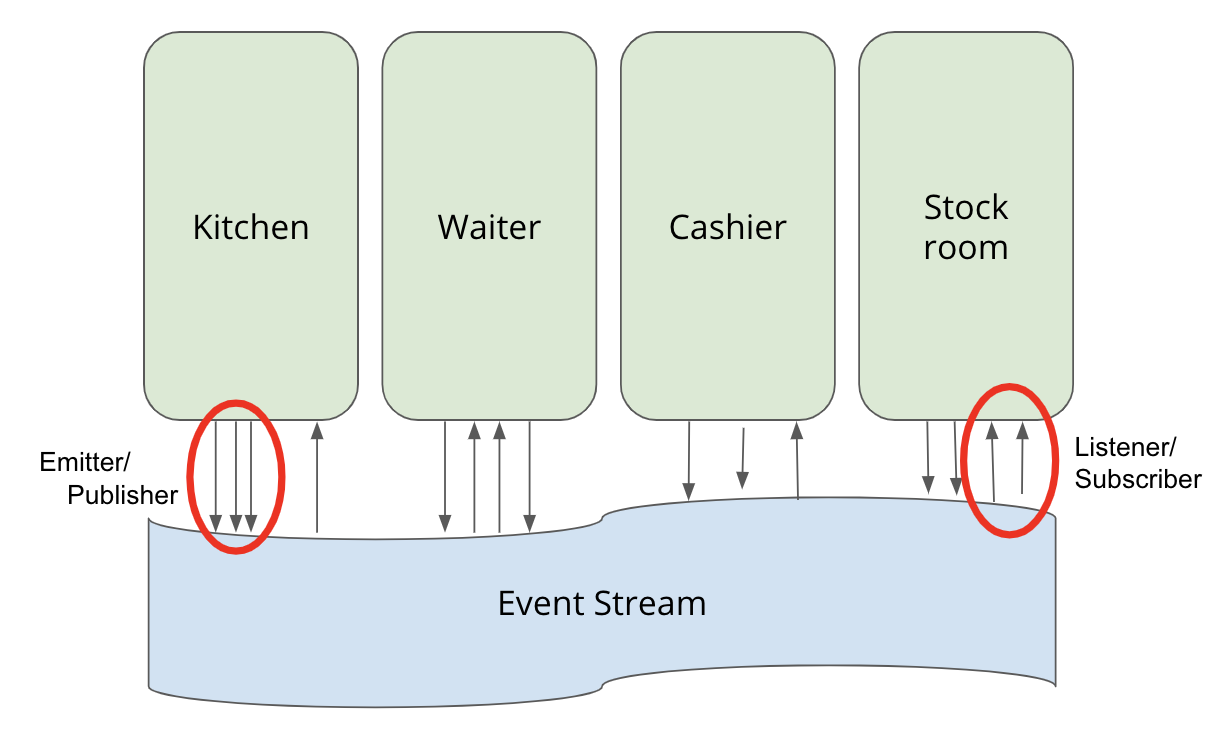

An event-driven system typically consists of event publishers (also called emitter or producers), event subscriber (also called listener or consumer or sink), and event stream (or event channel).

There are some important characteristics of an event. Primarily, events are things in the past. They are a broadcast message to the ecosystem that something has happened. Secondarily, these events should be recognised by our business as key events.

My colleagues Andrew Harcourt and Steve Morris have been propogating a nice pattern called Act Assert Announce that works well for Event Driven Architectures.

Eventual consistency

Eventual consistency is a consistency model used in distributed computing to achieve high availability. Eventual consistency informally guarantees that, if no new updates are made to a given data item, eventually all accesses to that item will return the last updated value.

Imagine when the Kitchen broadcasts the event “Steak and Chips for tabel 26”. The Cashier doesn’t have to act synchronously to update the bill, so long as that charge is on the bill by the time the restaurant-goer leaves.

(Below is my little rant about Eventual consistency)

The world is not synchronous, so why force your systems to be?

Somewhere along the line, we started to believe that all data updates had to be synchronous and that data couldn’t be inconsistent. But let’s look at what happens to data in the real world. When I moved house a year ago, my address was not changed everywhere simultaneously. I notified Medicare, my bank and my hair dresser with different urgency. These records eventually became consistent. And if I didn’t get to it before an important letter was sent, my postal redirect would catch it. The real world survives in an inconsistent state. So then why do we insist on Single Source of Truth? Why are our transactions atomic? It’s about time we embrace eventual consistency.

Commands, not passive aggressive events

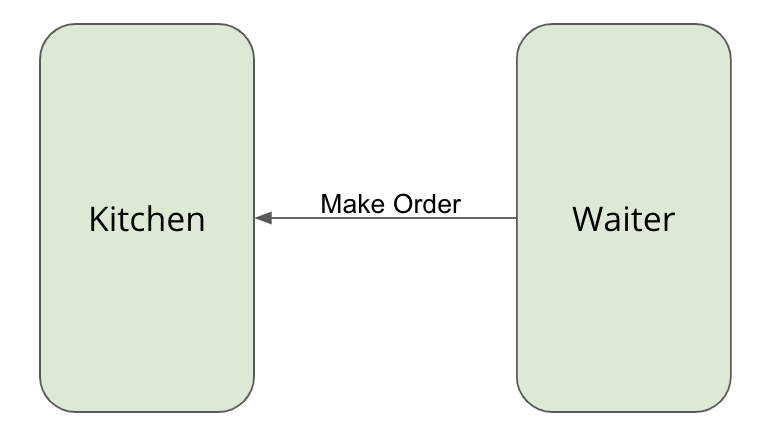

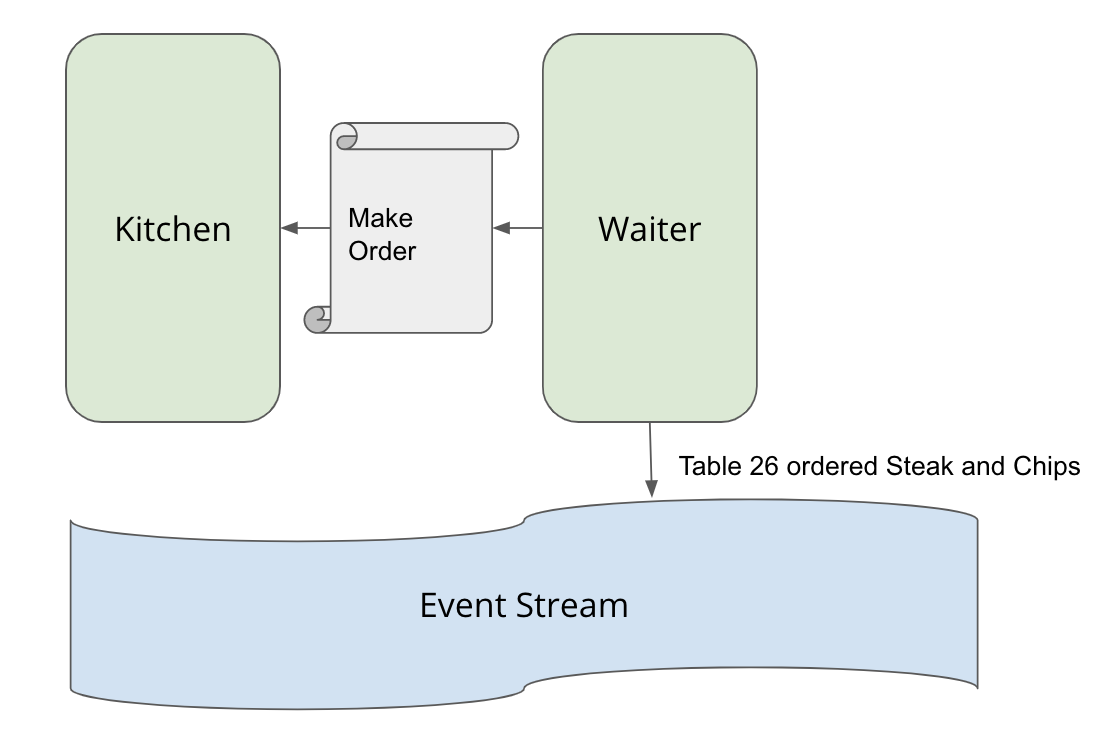

A step within a business process might require two services to interact. When our Waiter takes an order, it needs the Kitchen to start making it. One method is for Waiter to broadcast a Table 26 has ordered Steak and Chips event and expect the Kitchen to start making it. But we really need to make sure that Kitchen will act on that event, so really this is just the Waiter broadcasting a passive-aggressive event.

In these cases it is entirely appropriate for one service to issue a direct command to another service (eg Waiter calls the MakeOrder(Steak and Chips, table26) in Kitchen). This is far more preferable than publishing a passive-aggressive event, where a service expects an action to follow.

It’s possible that due to performance or other constraints, point-to-point calls are inappropriate (consider cases where a service is down). In these cases, we could consider publishing these commands to a queue and take advantage of the underlying Eventing platform. We should treat these commands separate to any event we might emit to the Event Stream,

Domain Driven Design (DDD)

In his seminal book, Domain Driven Design Eric Evans “explains how to incorporate effective domain modeling into the software development process”. The cornerstones of Domain Driven Design are: Ubiquitous Language (between “the business”, “the techies” and the code), Bounded Contexts (in which consistency is important only within the boundary), Building blocks (like Entities, Value objects and Aggregate Roots).

You can do Event Driven Architecture without it, but why would you? DDD gives us the tools to define our bounded contexts, which give us our services. Modelling the domain helps us identify the events that are important to the domain.

Inside the box/Micro Architecture

Command Query Responsibility Segregation (CQRS)

CQRS is a way to separate doing actions (commands) from read requests (queries). Although this style might seem obvious today, and contemporary frameworks have this as the norm, this technique was adopted in a time when services were not RESTful and actions and queries were all together in a request (if you’ve ever worked on a ASP codebase are you know what I’m talking about).

At an extreme, some implement this with separate deployable services for commands (things that change state) and queries (things that read current state). Technologies that support this approach include GraphQL and ElasticSearch.

I prefer to take a more tempered approach. Commands and Queries are served from the same deployable service. To enable the separation The service API follows RESTful verbs : POST, PUT and DELETE are used for Commands and GET is used for Queries. Although some systems enforce the separation of commands and reads in the controller (ie a controller only responds to Get and other controllers only respond to Post) we take a relaxed approach a mix these methods in the one controller.

Commands can be wrapped in a Commit Transaction, where Queries can be wrapped in a rollback transaction. Convention tests help us enforce this separation.

Event Sourcing

Event sourcing is a data storage technique that stores state changes as opposed to the current state of an object. Current state is reconstituted by replaying the state changes. This allows the system to not only know the current state but also past states as well.

A great example of an event-sourced system is Git. Git stores the delta commits, and calculates the current state by applying the delta commits (changes) from an initialised state.

Although it can work well with Event Streaming, it is important to note that Event Sourcing is a separate concept. Event Sourcing applies to the database (and the ORMs) and is therefore a concern of Inside the Box architecture.

Let’s consider our Restaurant. At night, the Kitchen is busy making orders and announcing “Steak and Chips for table 26”. The Stockroom could listen to each of these messages and reduce its Steak quantity each time it hears this event. But the Stockroom only orders in the morning. So instead, when it makes the order to restock, it replays all the “Steak …” events, as well as “Steak received” events to determine stock levels.

To Conclude

We’ve built up a nice little Restaurant system now, formed around our domain boundaries, broadcasting Events to each other, issuing commands when needed and event sourcing stock levels. Our system is easy to understand, no spaghetti communication between services and no centralized orchestration. We have easily developed and created nice isolated tests without requiring the whole restaurant to be assembled locally.

As you can see, all these concepts are complementary to each other, and whilst they have their differences, they work very well together. I hope this provides enough explanation of each to help progress you on your EDA journey.